Some of Kansas Athletic Director Travis Goff’s most significant moments in college athletics came when he was a 25-year-old director of development at Tulane, living in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina ravaged the city.

Goff, who spent more than 8 years at Tulane, considers himself to be in the top 0.5% of NOLA residents in terms of those who were the luckiest, the least-impacted or had it the easiest after Katrina hit, 20 years ago last month.

And while his apartment was not flooded and his car remained in the same spot he parked it throughout the storm, the moments, opportunities and experiences that followed the devastation around him were some of the most profound in Goff’s life. And all of them, good and bad, helped line the path that eventually led him to his first AD job at Kansas.

“I was just a punk taking orders and I didn’t even understand two-thirds of the picture of what they were trying to achieve.”

— KU AD Travis Goff on his time at Tulane in 2005

Last week, R1S1 Sports sat down with Goff to talk about that chapter in his life, his memories of Katrina and what came next.

The impact of Hurricane Katrina nearly ended the Tulane athletic department as people knew it. But Goff, under the guidance of then-Tulane AD Rick Dickson, was a part of not only keeping it alive but also helping Tulane’s athletes and sports programs “carry the flag” for Tulane as a university during that unimaginable time.

“I was a fundraiser largely,” Goff recalled. “And a big chunk of me thought, ‘Well, there’s a fundraising need, but the fundraising need we had after Katrina was far bigger than athletics, with help for the city and the university being far more important.’”

To that end, Goff said it was “crystal clear” that the moves made by Tulane athletics could not add any financial strain whatsoever to the university.

“That was a mandate,” he said. “And everybody understood that. Not even up for debate.”

Just over 300 student-athletes were evacuated and sent to other campuses that fall, and half of Tulane’s 16 varsity sports were temporarily suspended before being phased back in over the next four years.

Fifty percent of Tulane’s athletic department staff was also temporarily out of work — still on the payroll but not on the ground to aid recovery — and Goff was one of the lucky ones who got to keep his job in the aftermath of Katrina.

Not that the job was anything close to what he was used to doing.

More images of Tulane athletic facilities after the uptown New Orleans campus was battered by Katrina. [Tulane Athletics photos]

'Am I even willing to go do that?'

Back home in Kansas for a funeral when Katrina made landfall on Aug. 29, 2005, Goff recalls a feeling of uncertainty surrounding his immediate future as he watched the catastrophic images of the storm battering his new city surface on television.

After the funeral, he went to Kansas City to stay with his brother for a little more than a week, unsure of when or even if he would return to New Orleans.

“It was a blessing, in that regard, not to have had to evacuate,” he said of the timing of the funeral back home. “And then I, of course, was not one of the staffers who had to help mobilize the student-athlete population.”

Untethered, Goff easily maintained the perspective that things could have been worse for him. After all, thousands of people’s lives near his newly adopted home were turned upside down overnight.

Being back home, and with family no less, kept Goff calm during an otherwise terrifying time.

“I wasn’t defeated by any stretch,” he recalled. “But I was like, ‘Man, I don’t know if I’m going to get an opportunity.’ And then, if given the opportunity, am I even willing to go do that. It would’ve been a breeze to say, ‘You know what; let’s go do something else. I don’t want to do this.’ And I pondered that.”

So much so that he called current Ohio State AD Ross Bjork, a Dodge City, Kansas native like Goff, to see if there were any opportunities at UCLA, where Bjork was working as a Senior Associate AD.

Not long after that call, which yielded nothing, Goff received the call from Dickson, who told him to report to Dallas to get to work on moving Tulane forward.

For weeks, Goff, Dickson and five or six other Tulane athletic administrators operated out of the Conference USA headquarters, taking every day one small step at a time.

“It was never a woe-is-me deal at all,” Goff said. “I was like, ‘Gosh, I’m so lucky,’ and then I got that call that said be in Dallas tomorrow. There were only a couple of us that got the privilege to do that.”

Why Goff?

“Whether it was because he was scared to death or calm and not rattled, he impressed on me that I could count on this guy to stand by my side,” Dickson told R1S1 Sports during a recent phone interview. “We knew we were down (numbers) in that area and needed every hand on deck to help us on that front.”

The way Dickson put it, he didn’t need someone to steer the ship. And Goff certainly would not have been ready to do that. But he did need a crew. And Goff, like the others Dickson chose to have with him, carried a quiet confidence that pushed him through his fears and inexperience.

“It wasn’t, ‘I’ve never done anything like this,’” Dickson recalled of Goff’s attitude. “It was, ‘OK, what do we do?’”

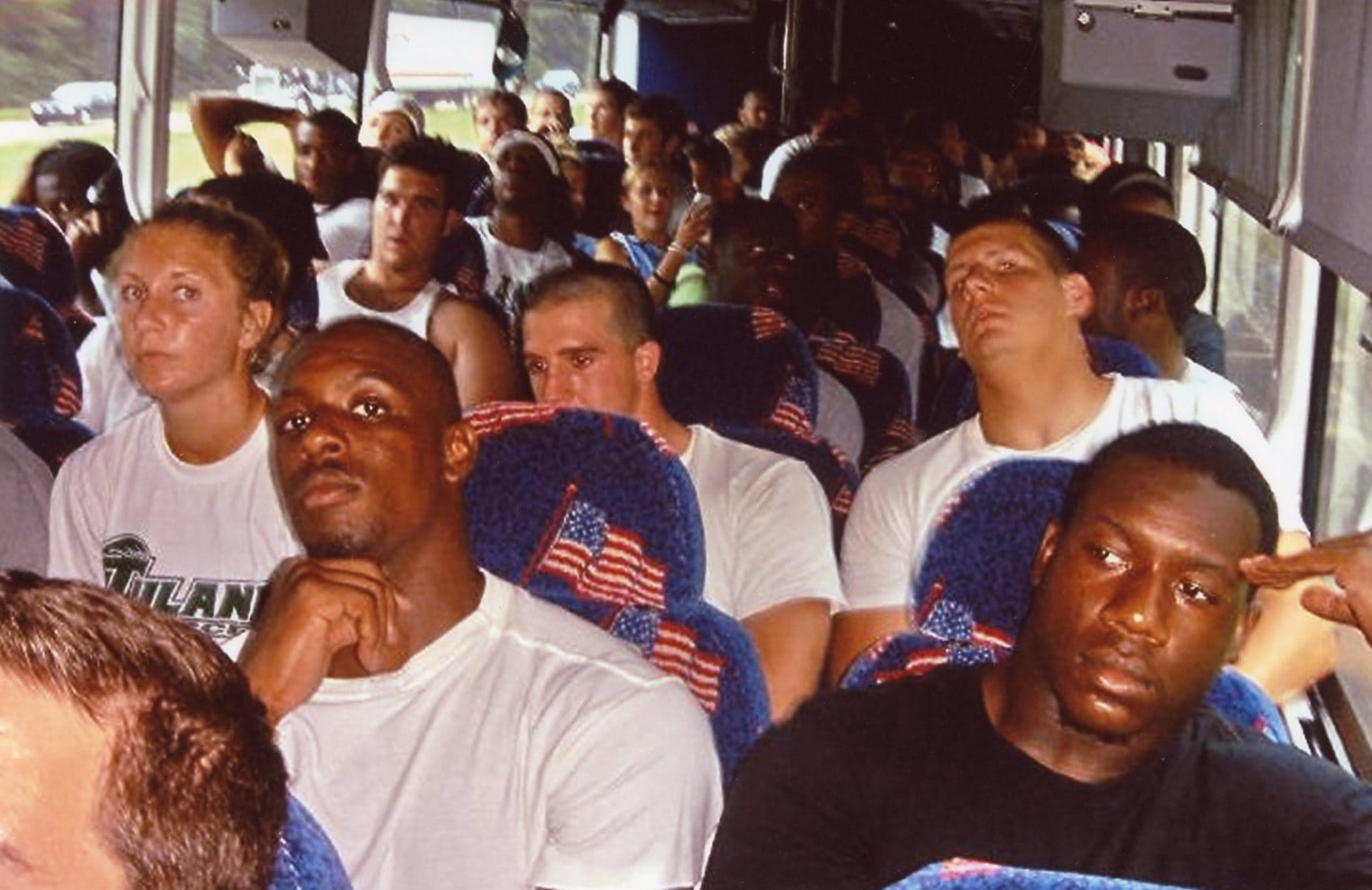

Tulane student-athletes, on buses and the gym floor with a puzzle to pass the time, in the aftermath of Katrina. [Tulane Athletics photos]

Doing whatever was asked

Primarily a fundraiser for the Tulane Athletic Foundation — TU’s version of KU’s Williams Fund — Goff, in his second year at the school, suddenly was managing people, organizing logistics, requesting donations for athletic equipment and part of a small inner circle that was charged with keeping the lights on, not just for the Tulane athletic department, but for the university as a whole.

“We were the one unit of the campus that was actually still acting,” Dickson told R1S1 Sports.

Dickson called the group he put together his “Mission Critical Team.” That collection of people, which included Goff, did everything from delivering meals and securing uniforms to planning for recovery, mobilizing athletes on seven or eight different campuses and trying to cobble together a vision for the future that did not involve closing the doors and watching Tulane resurface as a Division III athletic department when it reopened.

“You can either run from it or you do it,” Dickson said. “And that team chose to do it, which I’ll forever be thankful and grateful for. We all did a little bit of something and everything. And these things were being mapped out on a chalkboard in a hotel room and changing every 24 hours.”

A third of Tulane’s campus was under water, and most of that compromised 33% was athletic facilities.

Goff was just 25 years old then, making an annual salary of $31,099. He doesn’t remember leaning on any previous experiences to get through it, simply because he had nothing that came even close to comparing.

While he was still young, inexperienced and in many ways naive, the fact that even a seasoned-leader like Dickson was going through an ordeal of this magnitude for the first time bonded the entire team, with each of them pursuing daily the common goal of finding a way to keep people safe, steady and moving forward.

Knowing that Dickson and Tulane president Scott Cowen were on the ground, helping students evacuate as the water rose to 4 and 5 feet outside, Goff figured his part was easy.

“I mean, those guys were unbelievable,” he said. “They were awesome. And I was so blessed to witness it. I was just a punk taking orders and I didn’t even understand two-thirds of the picture of what they were trying to achieve.”

What he did understand was how to grind.

Goff managed and organized various groups when he was told to do so. He went to Dick’s Sporting Goods to ask for tennis rackets and shoes when it needed to be done. And he took on countless other tasks that had nothing to do with the fundraising he went to New Orleans to do.

“I was doing whatever was asked of me,” Goff told R1S1 Sports. “I vividly remember being sent a spreadsheet and told to work with the equipment manager to figure out how to equip all of our teams, literally just making sure our student-athletes had something to practice in and something to compete in. Very seldom was there talk about, ‘People won’t help us.’ It was a lot more of, ‘Gosh, this is amazing.’ In fact, one of the challenges we faced was how do we manage all of the offers from people constantly reaching out to offer their support.”

He continued: “We had a checking account that, what I remember being told, had about $500,000 in it; and that’s what ran that athletic department for a fall.”

Things did run, albeit in a different way than anyone had seen before or has seen since.

Spread out across campuses at Louisiana Tech, Rice, SMU, Texas A&M and Texas Tech, Tulane athletics moved forward with football, swimming & diving, volleyball, women’s soccer, baseball, women’s basketball, men’s & women’s tennis and men’s and women’s golf as the only active sports.

That’s to say nothing of the countless other campuses that took in Tulane students who were not athletes, free of charge, for a semester so that Tulane could use their tuition money to get back on its feet.

“That dynamic happened, which was critical for the university to survive,” Goff recalled. “And the other thing that is a pretty strongly held belief is that if the student-athletes didn’t compete that fall, Tulane would’ve never been able to justify continuing as a Division I athletics program.”

'If you only knew'

While each sport and several of the individual athletes received Goff’s attention, his initial memory 20 years later quickly goes back to two of them — football and women’s basketball.

With the Kansas football program having to play its home games in Kansas City during the 2024 season while construction on the new David Booth Kansas Memorial Stadium was ongoing, Goff said he remembered hearing someone on KU’s staff note that the Jayhawks basically had 12 road games last year.

“And I kind of quietly thought to myself, ‘If you only knew,’” Goff said. “Eleven games in 11 stadiums — the first and only time that will ever happen — with barely enough equipment and buses and living in a condemned dorm like those football student-athletes at Tulane in 2005. That was the ultimate.”

“I didn’t do that,” he added. “I didn’t live in a condemned dorm in Ruston, Louisiana. I lived in an apartment in Dallas. And student-athletes three or four years younger than me had to be leaders in as challenging of an environment as anybody. I just went along for the ride and did what was asked of me.”

“Vagabonds,” Goff called the 2005 Tulane football team.

“Get on a bus,” he began. “Every game was a road game. And many of these kids, as you can imagine, had family members that they were just trying to locate and find out if they were OK and stay in touch with — real human life concerns. But they did it and they represented for Tulane. In a lot of ways, they saved an entire athletic department.”

The women’s basketball memory is a little sweeter.

See, that winter, the Green Wave women’s hoops team was the first college or professional sports team to host a game in New Orleans after Katrina.

Dec. 18, 2005 was the date of the Green Wave’s 72-60 home win over Central Connecticut — after four games in Texas and two more in Arizona to open the season — and Goff will never forget the feeling of being there.

“It’s not like there was a big crowd,” he said. “But, boy, was that an incredible representation of resolve and a moment that said, ‘You know what, this thing can persist and continue forward.”

In a much smaller way, he likened that night to the feeling people across the country seemed to have four years earlier, when President George W. Bush threw out the first pitch at Yankees Stadium before Game 3 of the 2001 World Series, less than two months after the terrorist attacks on 9/11.

“In a local lens, within the small community following Tulane athletics, it felt like that,” Goff said.

Valuable lessons learned

Goff first returned to New Orleans in early November of 2005, finding his apartment dry — a half mile from campus — and his car in the same spot he left it.

The U.S. National Guard still patrolled the streets and were often the only ones outside. You had to have permission to enter certain parts of the city and you had to follow a strict schedule, during daylight hours, for when you could be there to get what you needed.

By Thanksgiving Goff was back in New Orleans for good. And he stayed another 7 years after that. During that time, as his roles and responsibilities grew, he found himself in charge of leading the fundraising campaign to raise $70 million for Tulane's brand-new, on-campus football stadium, Yulman Stadium, which opened in 2014, after Goff had left for Northwestern.

Prior to the new stadium's arrival, Tulane football played its home games at the Louisiana Superdome in downtown New Orleans.

It was special for him to go back there in 2022, when the Kansas basketball team won a national championship in New Orleans, the city where he grew up and met his wife and had some of the most profound experiences of his life, both personal and professional.

And he carried several post-Katrina life lessons and professional precedents with him to Northwestern and Kansas, where he continued to climb the ranks and grow as a leader and athletic administrator.

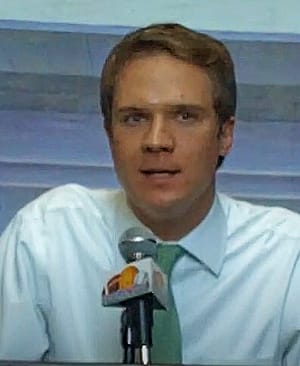

KU AD Travis Goff, shown before 2024 Kansas football games at Children's Mercy Park (left) and Arrowhead Stadium (right), where the Jayhawks played while construction was ongoing in Lawrence. [Chance Parker photos]

Goff will tell you that he’s still a work in progress and that, at age 45, — he’ll be 46 in two weeks — he still has so much growing to do.

But he’ll never forget the ways that being in New Orleans after Katrina helped jumpstart his career and his appreciation for the little things, in both life and the industry.

He used to think you had to try to control every situation. Now he believes adaptability is crucial. He used to stress about almost every obstacle and each tough day. Now, he leads with more positivity and optimism than ever.

Both traits served him extremely well during the past couple of years as KU upgraded its own football facilities and managed the disruptions that came with the work.

At no point in the past 20 years, does Goff recall ever having a moment where he thought to himself, “Yeah, Katrina taught me that.”

“I didn’t know if I was learning much when I was working on a spreadsheet around equipment,” he said. “I don’t think I was thinking, ‘I’m changing the game here and I’m growing immensely.’ It was more like, ‘This is what we need to do and I’m gonna have to do whatever I have to do.’ You can’t get that in a classroom and you can’t get that through years or even a lifetime of work.”

In reflecting back on the 20-year anniversary of the monster hurricane, he found it easy to see how much those days still mattered in his life.

In many ways, what went down in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and with Goff’s role in helping Tulane survive mirrored the philosophy that Hall of Fame Kansas basketball coach Bill Self attaches to his annual preseason conditioning stint known simply as "boot camp."

Each year, Self and his coaching staff strive to make boot camp so challenging and so difficult that those who conquer it are able to move forward with the belief that everything that lies ahead will be easy by comparison — practices, games, adversity, opponents.

“Travis experienced the Katrina boot camp,” Dickson said. “And he grew up pretty quickly. It’s been one of my greatest prides of joy to see what he’s evolved into and is blossoming into, while doing it at an iconic university that also happens to be his alma mater. You couldn’t script it better. He would tell you he was fortunate, but I’d tell you they’re pretty darn fortunate, too.”

True to his nature, Goff tried to downplay the idea that he did anything special back in 2005, deflecting the lion’s share of the credit to Dickson and the rest of the team and those Tulane student-athletes who he said were the true warriors and heroes of the catastrophe.

“If there’s anything to this story, it’s that Travis Goff gained more from Katrina than he had taken away,” Goff said with added emphasis. “And that’s a weird dynamic because my career opportunities grew exponentially because I was there at that time and because I had a chance to stay. I truly was just there, though, and wow; what a story. I consider myself lucky to have been even just a tiny little piece of it.”

— For tickets to all KU athletic events, visit kuathletics.com